In 1963, Stanley Milgram, Professor of Psychology at Yale University, conducted a series of experiments to test human responses to authority. Inspired in part by the trial of Nazi war criminal and Holocaust architect Adolf Eichmann, Milgram wanted to understand what made seemingly ‘normal’ people carry out horrifying and barbaric acts. What, Milgram wondered, was the effect of authority on human behaviour. Milgram’s most famous, and most shocking (although not literally), study was known as Experiment 18: a peer administers shocks. The set up went thusly…

Milgram sought 40 participants from the general public to take part in a piece of scientific research. The participants were told that the experiment was about teachers and students. The supposed test subject, the student, was actually a stooge or confederate in the experiment, while the participant, in the role of teacher, was the actual subject of the experiment. The participant was required to wire the ‘student’ to a set of electrodes, and then move to an adjacent room from where they would ask the student to match pairs of words.

Wiring up. From L-R above: Participant (test subject), stooge, Milgram

For each incorrect response, the teacher was required to administer a steadily increasing voltage of electric shocks. Whenever the teacher hesitated from administering the shock, Milgram, as the authority figure, would direct them to continue using one of four verbal commands, on an increasing scale of authority:

- Please continue.

- The experiment requires that you continue.

- It is absolutely essential that you continue.

- You have no other choice, you must go on.

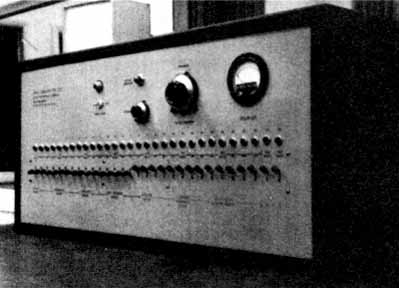

In reality, Milgram’s ‘shock generator’ was nothing more than an empty box with some switches and a scale of increasing ‘voltage’, from 15 volts, all the way up to 450 volts, which was worryingly labelled XXX:

The Shock Box and scale

How far would the participants go in administering ‘shocks’? Incredibly, 65% of the participants went all the way, administering the full 450 volt shock. They couldn’t see the reaction of the student stooge – he was of course perfectly fine – but he did provide a set of verbal responses to the shocks from simple grunts, all the way up to a thud followed by silence. Perhaps even more worryingly, none of the participants who refused to administer the final shocks insisted that the experiment itself be terminated, nor left the room to check the health of the victim without requesting permission to leave. In fact, of the 40 participants, only 2 refused to administer any shocks at all: one was a qualified electrician, the other was a Holocaust survivor.

COMPLIANCE

Craig Zobel’s new film Compliance is Milgram’s experiment writ large. In a perfectly ordinary town in Midwest America, on a perfectly ordinary day, at a perfectly ordinary fast food restaurant, manager Sandra is having a bad day. Somebody left the freezer open the previous night and $1400 of stock has been spoiled. Not what you need when you know business is going to be brisk, her young serving and catering staff are not wholly reliable and, if the rumours are to be believed, a secret shopper is coming to visit. And then Sandra receives a telephone call from a police officer claiming that one of her staff, 19-year old Becky, is suspected of theft from a customers purse. The officer has the restaurant under surveillance as part of a wider investigation and he needs Sandra’s help to investigate the alleged crime. What subsequently transpires is a shocking and utterly compelling study into the human tendency to obey authority. This is by no means an easy film to watch, indeed it is one of the most uncomfortable cinema experiences I have ever had, and it would be wrong to describe it as entertainment. Nevertheless, Compliance is a compelling and important film, one that I have no hesitation in recommending, which stands as a salutary lesson that we should always be prepared to challenge authority, lest we lose that which makes us compassionate human beings.

Make no mistake, Compliance is not a documentary, it is a dramatisation of actual events. But it is all the more powerful than a documentary film would have been in my opinion. Consider also that nothing portrayed on screen has been exaggerated – it really did happen. Maybe not in that particular midwestern town, maybe not to Becky and maybe not to Sandra. But it happened nonetheless.

Would you comply? Who knows what we each might do in similar situations, but Milgram’s experiments have been reproduced since in various forms, both in the lab, but also in the real world (try Google-ing the Stanford Prison Experiment for another example of obedience to authority in a total situation). Sometimes people are simply rotten apples. However, perhaps more often, people are actually perfectly good apples, they just happen to be in a rotten barrel. That is the lesson we should take from Compliance.